The Inner Game: Failure Is Not An Option

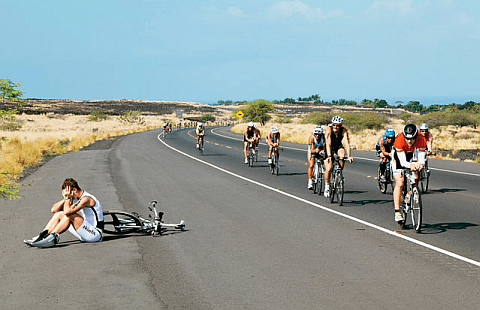

Part of the process we engage in when we take part in sport is the process of self-improvement. While it looks like all we need is physical training to achieve our goals, in truth the more we go at it, the more we begin to understand that what’s really holding us back are mental and emotional patterns of thinking and reacting to the hurdles we encounter on the road to success. One of those hurdles is how we respond to setbacks and disappointments.

Without getting too philosophical about things, here’s our advice when it comes to moving past the inevitable setback and disappointment.

+++

Hi Athlete X,

Sorry to hear you had a bad race. That is part of the sport, fortunately — if we weren’t challenged by the races we’d get bored pretty quick. I can’t think of any top pro who hasn’t had to face total disappointment and make the decision to rally his resources and carry on. Chris McCormack walked his first attempt at Kona. Norman Stadler took 17 years in triathlon to finally win the Big One, and Mark Allen raced in Hawaii 10 times before he first won.

I attended several world championships at the elite level. My races were usually quite a disappointment and after years of hindsight I eventually put my finger on why. The reason was: Illusion and Pressure. The illusion had as much to do with my own abilities and athletic maturity as it did with the idea that somehow a world’s race is different from others, and that we should prepare for it somehow “differently” as a result. This adds to the pressure we feel already, having investing our eggs of time, energy and effort into the basket of “that one race.” Add it all up and you get the perfect recipe for a disaster — high expectations and poor readiness (due to experience or lack of appropriate mental preparation, which often includes a good dose of humility in the past).

In fact, world’s (or the Olympics, or Kona) are no different than any other race at all. If you want to excel there, it’s not just about training as you normally would, but also approaching the race as relaxed as you normally would any other race. The athletes who fare worst at world’s generally fall into one of two groups: There are the ones who “make the most out of it” by seeing the sights, attending the parade, the banquets etc. — they appear relaxed on the one hand, but underneath they are simmering in anticipation. These athletes try to diffuse the tension by distraction, exposing themselves to all kinds of “noise” and instead amplifying their apprehension when in fact a bit of a “triathlon withdrawal” until race day would be the appropriate preparation. Prescription: Mini-golf instead of past party, movie instead of parade.

Then there’s the athletes who are highly nervous about the race and have been “amping up” towards race day for a long time. A bit of camaraderie and talking openly about your nervousness won’t hurt — you’ll see you’re not alone. When you see that, you can place yourself in the “everything’s normal, it’s all just part of the process” basket and shed the anxieties by looking forward with eager anticipation instead.

Without the practice of racing at high pressure events (the big ones) over and over again, that pressure cooker situation never becomes a normality and we can’t ever adapt to those feelings or recognize the pattern and wasted energy. Over time when you keep at it, whether it’s heading to your first big international races, toeing the start line as a pro, then as a competitive pro and finally the favourite, or as an AG’er in a similar situation, putting yourself through the cycle of experience to learn your feelings and reactions is a critical part of the improvement process. Eventually you can come to drop the habits and patterns you recognize as negative by understanding through their very familiarity that they’re just baggage, along for a free ride. Shed your expectations to do anything but your best and decide to let the results be what they may — and you’ll drop these unwelcome feelings right away.

How we approach the race has a lot to do with the outcome — the top athletes in the world constantly demonstrate humility and show that any human on top of their game should prepare to be humbled at a moment’s notice. And then, when the dust has cleared, they gather themselves up, look forward and go about the process of trying again, fine-tuning and improving. Don’t look back unless it’s with the intention of gathering useful information to help you improve going forward. The past

You have every business being at the world championships. You qualified, just like anyone else. Whether you choose to go back or not is entirely up to you — if you do, you will take this experience with you just like any other leading up to this. So it might as well contribute to your improvement!

My personal results at world’s the first time ’round, when I went from big fish in a little pond to minnow in an ocean, taught me that there are a lot of people who were more capable of handling high pressure races, and that their physical preparation was every bit as good as mine, and mostly much better — and that I needed to work on many aspects of my attitudes and expectations if I wanted to improve on the world stage.

We have a saying that the champions separate themselves from the ordinary not because they don’t experience disappointments, frustrations and challenges to overcome in life, but in how they overcome these challenges. If you let yourself come down this far from having a sub-par race, you risk “anchoring” yourself to this experience and the feelings around it. To move on, it might be as easy as telling yourself: I gave it my all. I raced, I qualified, I trained hard, I went to the race, I did my best on the day. All reasonable effort was made without disrupting my happiness elsewhere in life, and my race was the best I could do that day. Amen!

We also remind ourselves that success can only be measured by the obstacles we overcome — reading a result out of this context means very little. Family, work, high demands on our free time and so on are all challenges we face that need to be incorporated into understanding our efforts. Better to identify what was positive about the experience and hang onto that than to carry the burden of disappointment around forever — there is nothing to be gained by that.

I had several hugely disappointing races in my athletic career. Racing from prize purse to prize purse, when each podium counted to pay the rent, and taking a year off career and work to invest in training and then having major DNF’s at my goal races all taught me a thing or two…about triathlon, about the world, but mainly about myself and the cracks in my character that kept me from achieving everything I dreamed I could or thought I could. The work is the work — anyone can be coaxed enough to complete it. But that is only the beginning.

As they say, the road to success is paved with failure. If you can remember that, then you will never encounter this illusion of “failure.” Instead, you will live a life filled with learning and a natural effort to improve and an underlying attitude of curiousity: “What can I learn from this? What happens next? How will this help me going forward?”

There’s nothing more satisfying in the end than saying you gave it your best. Nothing else will ever take the place of that, not even hollow victory. If you can look at yourself in the mirror and say you did your all then you can move forward and make use of your experience and improve at your next attempt, whether it’s triathlon or any other situation where you open yourself up to possible failure and leave yourself exposed to potential disappointment.

That’s called courage.

SWIMBIKERUN.ph / Ironguides